Idaho National Guard Soldier spent 309 days as a prisoner of war

Capt. Robert Taylor

Idaho National Guard

Ray Servatius has a lot to think about at night. Mostly he thinks about that day in Korea when his plane was shot down. The pilot was likely dead before the plane hit the ground. Another Soldier was killed trying to reach him. He spent the next 309 days as a prisoner of war.

“What if I had stayed in that plane 20 more seconds?” he said. “I’d be like the pilot. What if I had jumped earlier? What if my gun had ammo in it? I have a lot of thoughts like that.”

Despite those questions, Servatius said he’s lived a pretty normal life since returning home to Clarkston, Washington, in 1953, shortly after the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed.

“I met this nice lady from Lewiston and married her,” he said. “We had three kids and had a pretty normal life after that.”

“WHERE MY FRIENDS WERE”

Servatius was 19 when he enlisted into the Idaho Army National Guard’s 1st of the 148th Field Artillery Regiment in 1949. The unit, now located in Eastern Idaho, was located in Northern Idaho at the time and Servatius lived in Clarkston, just miles across the Idaho border. “That’s where my friends were,” he said of joining an Idaho National Guard unit despite living in Washington.

“That’s where my friends were,” he said of joining an Idaho National Guard unit despite living in Washington.

It was also the unit his younger brother, Fred, enlisted in just before the unit deployed.

The 1-148th Field Artillery was activated in May 1951 and sent to Camp Carson, Colorado, for training.

The Idaho National Guard’s 116th Engineer Battalion, the 190th Fighter Squadron and the 25th Army Band also activated during the conflict. Only the engineers would deploy to Korea as a unit. Soldiers from the 1-148th were broken up and sent to units already in Korea. Half of the unit remained stateside.

Servatius attended a fire direction school and additional leadership training before being sent to Korea. After all that training, he said he was happy to be heading to Korea in April 1952 and that he was anxious to get going.

“Young kid’s foolishness,” he says, looking back nearly seven decades later.

Servatius, 22, was a sergeant assigned to a field artillery unit in the 7th Army as the head of a survey section. He said there wasn’t much for him to do since the battalion was in a permanent position and didn’t move the three months he was there.

In July, the Air Force asked for volunteers to fly as aerial observers. He was the only Soldier from the 7th Army selected.

“I don’t know if that was dumb luck or poor luck,” he said.

IN THE SKY

As an aerial observer, Servatius flew with the 6147th Tactical Air Command. He would fly with an Air Force pilot in a T-6 Texan, a single-engine plane used primarily for training new pilots.

Servatius’ job was to sit in the back seat and observe targets for fighter planes or bombers. A command post would give the crew a target. The crew would fly to the location, observe it, report what it could see to other pilots and mark targets for bombing using smoke. After a bombing run, Servatius and the pilot assigned to fly the T-6 would fly back over the target to assess for damage and determine if additional bombs were needed.

Servatius flew 60 missions between July and Oct. 24, 1952. On Oct. 23, he completed a mission with Capt. Wilbur Darby. The flight began in the afternoon but by the time the pair completed their mission, it was too foggy for Darby to return to base and instead were directed to spend the night at a different base.

Darby, a B-24 pilot during World War II, had earned the Distinguished Flying Cross after sinking a Japanese freighter he encountered on a lone mission. He was from New Jersey and was married with three daughters between the ages of five and eight.

On Oct. 24, the pair left the airbase to complete their second mission together. Upon mission completion, Servatius said Darby realized he left his pistol at the base where they had stayed the night before. The pair returned to retrieve it and shortly after were assigned a third mission together. It would be 48 years before Darby’s family would learn the details of their final flight.

CRASH LANDING

The mission was to observe Chinese artillery positions for four F-86 Sabres. Darby and Servatius located the target and directed the fighter jets to it. As they were circling the target to assess for damage, anti-aircraft fire hit the plane.

“It sounded like a .22 bullet going through a tin can,” Servatius said.

Servatius then called over the radio that the plane had been hit. Darby did not respond.

The plane then started to burn. Once again, Servatius called out for Darby over the plane’s intercom. Darby still did not respond.

Servatius then released his seat belt, opened the plane’s canopy, stood up and jumped.

Servatius said his parachute barely had time to open before he landed. He immediately realized he had landed on the Chinese side of “No Man’s Land.” He took off the bright blue flight suit he wore over his Army fatigues and noticed his left leg was broken and his right leg wasn’t much better. He isn’t sure if he hit his legs on the plane’s canopy or its tail once he ejected.

He could see his plane on fire and hear artillery bursting all around him. Servatius said he later learned from an Army buddy the artillery was dropped to keep nearby Chinese soldiers away from him. Another Soldier watched his plane crash from an outpost. Four days later, that Soldier, Sgt. Fred Servatius, learned he had watched his brother’s plane get shot down.

After a few minutes, Servatius heard a helicopter coming and thought it was his ride back to base. He watched them land near his plane and pick up Darby’s body. Then the helicopter left.

“THEY WOULD HAVE KILLED ME”

Servatius then started crawling towards the plane. He quickly ran into Sgt. 1st Class Charles Whitaker.

In 2002, Servatius learned Whitaker was in charge of a patrol and saw Servatius’ plane go down. He had been the one to call the helicopter to retrieve Darby. He also saw Servatius’ blue flight suit and assumed it was Servatius’ body. He was on his way to retrieve Servatius’ body when the two met.

Servatius said Whitaker told him Chinese soldiers were nearby and to get his .45 pistol out. As he cocked his weapon, he realized the magazine was missing. He believes it likely fell out when he ejected and hit his legs on the plane.

Chinese soldiers then ambushed the two. Servatius saw Whitaker get hit and never saw him again. Because Servatius’ pistol was empty, he couldn’t fire back at the enemy. After Whitaker was shot, they quickly took Servatius prisoner.

“If I had had ammo and shot back, they would have killed me,” he said.

Whitaker was killed during the firefight. He was 27. His body was found next to the plane’s wreckage a few days later.

PRISONER OF WAR

Servatius was unable to walk due to his broken leg so he was ordered to crawl up a steep hill. He was taken into a cave filled with Chinese soldiers where one of them tied a board to his leg. At dark, Servatius said he was carried on a stretcher by four Chinese soldiers all night. The next day, they stopped at a house where he was interrogated and forced to stay awake all day. At nightfall, he was moved to a POW holding place.

Servatius remembers being held in a hole dug in the side of a hill with a log roof and a front wall made of four small logs with a wooden door. The makeshift prison held 10 American Soldiers and eight South Korean soldiers with just enough room for everyone to lay down if they all laid on their sides. Servatius said there was only a small hole in the front and that it was dark most of the time.

The POWs ate rice twice a day. There wasn’t any water for hygiene and lice and other sanitary issues were prevalent. Soldiers used a single can for a latrine. Each Soldier was given one blanket, which Servatius said was never cleaned and was his only source of heat as temperatures regularly dropped below zero.

After two months, Servatius said he was moved to a POW camp. By then, his leg had healed enough to stand on. The trip took several days and Servatius said it was cold and he suffered frostbite on his toes during the trip.

Servatius was taken to what was known as Prison Camp Number 3 on the Yalu River. He said he could see into China across the river. The camp had approximately 200 soldiers from multiple countries. Servatius said the living conditions were better than his previous location. They were confined to Korean houses but had to sleep on hard floors. Food was varied but consisted mainly of rice. Soldiers dug trenches around the compound and hauled firewood in from nearby trees during the day. A creak provided Soldiers with water to wash and stay clean.

Soldiers were also given communist pamphlets and interrogated regulary. Servatius said interrogation efforts were mianly focused on younger or undereducated Soldiers in an attempt to get those Soldiers to defect. No one in the camp defected.

In February 1953, both sides exchanged sick and wounded prisoners. One released Soldier, Pvt. Walker, called Servatius’ parents when he reached the States. It was the first update they received on their son’s whereabouts and conditions since being notified he was captured.

On July 27, the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed, bringing an end to the Korean conflict. The POWs had no way of knowing what was happening outside their camp. However, Servatius said the local area normally remained dark after 10 p.m. but that night he could several lanterns burning bright throughout the area. A Chinese officer notified the Soldiers that a peace treaty had been signed and that they would be going home.

The Soldiers remained in the camp another three weeks. Red Cross care packages provided Soldiers with basic necessities during that time. Soldiers were transported across Korea in trucks and Servatius said locals threw rocks and other objects at them in every town. The trip ended with a four-day train ride and then the POWs waited another six days to be released, crossing over a bridge at Imingak over the Imjin River.

HEADING HOME

Servatius was released on Aug. 29, 1953, 309 days after he was captured. He weighed 135 pounds, 45 pounds less than before his capture.

Servatius and other POWs took the USS General W.M. Black to San Francisco.

“They said we’d go home first-class,” he said. “What that meant was that there was a man to every other bunk in the ship instead of every bunk.”

Servatius was diagnosed with tuberculosis in his lungs and left shoulder. He was expected to recover in Seattle but was assigned to a hospital in Spokane to be closer to his home. Once in Spokane, he took a bus to Clarkston, arriving close to midnight. A friend with a taxi cab gave him a free ride to his parents’ house. That night he slept in the back of a family car because his parents had gone to Seattle to meet him there.

LIFE AT HOME Servatius got out of the Idaho Army National Guard shortly after returning home. He was the only 1-148th Field Artillery Soldier who was a POW in Korea. During the conflict, 7,245 American service members were captured. 2,806 of them died in captivity, 670 escaped and 21 defected. Nearly 40,000 Americans died during the conflict and more than 7,800 remain unaccounted.

Servatius got out of the Idaho Army National Guard shortly after returning home. He was the only 1-148th Field Artillery Soldier who was a POW in Korea. During the conflict, 7,245 American service members were captured. 2,806 of them died in captivity, 670 escaped and 21 defected. Nearly 40,000 Americans died during the conflict and more than 7,800 remain unaccounted.

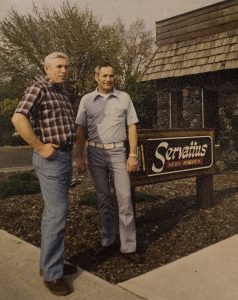

Servatius returned to the job he had before deploying to Korea, working for a wholesale magazine distributor. Six months later he and Fred bought out the distributor’s owner when he was ready to retire and ran Servatius News Agency together until 1998. Fred passed away in 2015 at the age of 82. Servatius married his wife, Carol, in 1954. The two remain married and have three adult children. He turned 90 earlier this month.

Servatius married his wife, Carol, in 1954. The two remain married and have three adult children. He turned 90 earlier this month.

In 2000, Darby’s family learned about his final flight when an officer with the Rutgers University Air Force ROTC program contacted Servatius looking for any information he could remember about Darby.

Servatius recalled flying with a different pilot almost every flight. He had been unable to remember the pilot’s name on his final mission and wasn’t sure who to contact to find out. He told the officer everything he could remember about Darby’s final days.

That officer conveyed his story to Darby’s wife and three children. His family knew he had been shot down and killed in action, but they knew very few other details. His daughters named their children after their father, passing on Darby as either a first or middle name in his honor.

In 2002 the ROTC program dedicated a Korean War monument in memory of Darby and the program’s Air Force ROTC’s honor society is named after him. Darby graduated from Rutgers in 1940. In 2003, the Clarkson City Council proclaimed Sept. 19 as Ray Servatius Day to mark the 50th anniversary of the battalion’s deployment and reunion.

In 2003, the Clarkson City Council proclaimed Sept. 19 as Ray Servatius Day to mark the 50th anniversary of the battalion’s deployment and reunion.

During the reunion, Maj. Gen. John Kane presented Servatius with the Purple Heart and Prisoner of War Medal, neither of which he had previously received. Kane served as the adjutant general of Idaho from 1995 – 2005.

Official Government Website

Official Government Website